There’s a scene in Alan Bennett‘s semi-autobiographical play The History Boys where two teachers are discussing the English language. Hector, played by Richard Griffiths, remarks to his colleague that he loves language. Not merely “words”, he says. “That would be so… Welsh!”. They both chuckle.

I wasn’t able to quote that one exactly as I watched it on TV back in Christmas 2007. But disregarding for now the possibly that Hector might not know an englyn from an awdl, there seems to be a grain of truth in that comment.

It’s also my warning shot for what follows. This post has more of my highly personal perspectives on learning the Welsh language, following my first post on that theme. Below contains PIECEMEAL DISCUSSION OF INDIVIDUAL WORDS. If you’re a Welsh speaker, I guess you should substitute “warning shot” back there for “bait”. Words? You LOVE IT.

If you don’t love it, start your own blog because I’d like to read more Welsh language blogs.

Anyway. I got through wlpan and am now on the pellach course. Despite my shortcomings, language is a general interest of mine. I often think and talk about the English language. It’s one of my favourite subjects. But Welsh speakers totally rule on this one. They talk about their language A LOT. And now, it’s starting to feel like my language too in some ways – so I gladly follow suit.

“But Welsh is such a difficult language to learn”, people tell me. They’re right in some ways. ALL languages present difficulties; Welsh has its own. Written Welsh uses the Latin alphabet which can be deceptive – it’s immediately familiar but rendered differently. Comparisons to English are inevitable and understandable. If English is all you have in your toolkit, of course it’s going to look strange. That’s what the learning stage is all about.

English is a pretty versatile and useful language. I like English. Actually I love it. Although I imagine it’s a right bitch to learn as an adult. Irregular verbs, wonky spellings, arbitrary plurals, bits of Saxon, Greek, Latin and French all mashed together. Fortunately I started learning English as a baby and freely enjoy all the benefits it brings, with none of the confusion of, say, whether to use “bring” or “take”. Or what exactly the word “it” means and to use it.

So right now I’m missing the word “it” because my brain fibre seems to have wired itself around the word. So I’m in a process of unravelling some of that and wrapping it around Welsh, which uses different structures.

Check a Welsh-English dictionary for the “it”-shaped hole.

Neither can I say “I don’t mind if I do”, one of my stock phrases when offered, say, a chocolate digestive. All I get is blank faces or laughter if I use “dw i ddim yn poeni os dw i’n wneud“.

Well, it’s nice to be of some amusement.

“But aren’t the dialects in north and south Wales, like, TOTALLY different?”, I hear them cry. No, not at all. It’s one language. Although some of the Gwynedd and Ynys Môn folk have put my confidence here through some rigorous testing, it must be said.

For a few days into wlpan last year I thought I was learning south Wales dialect. Fine. I live in south Wales. My dad’s parents were from Cwmaman which is perhaps where I could be if they hadn’t moved to Slough in the 1940s to find work, along with countless others. South Wales dialect? Here’s my 400 quid. Bring it.

Then I gradually realised it’s partly some kind of bizarre learner’s dialect with bits of schoolly official words that you hardly ever hear (sglodion and micro-don are two examples from the kitchen of nobody I know) and “proper” phrase structures.

But mainly, because I’m in Caerdydd, Y Mwg Mawr, I’m over in Dempseys / Mochyn Du / Clwb Ifor Bach and picking up Welsh words and phrases from all points of the compass. As my tutor remarked, purely in reference to Welsh and not even in jest – Cardiff is VERY cosmopolitan.

Each of my carefully plotted utterances could involve a word choice, such as teisen/cachen (cake), becso/poeni (worry), nawr/rwan (now) and llaith/llefrith (milk). The latter is an age-old shibboleth which verges on some miniature holy war at the breakfast table. My inclination would be just to adapt and pick one for the situation, in the same way I’ll just say cellphone to Americans like some accomodating chameleon. Everyone’s mate, see. Kindly pass me the milk and let’s get on. Dim siwgr diolch.

The only current exception is losin (sweets). That one’s hyper-regional and I’ve heard not only that but pethau da, fferins, da-da and melysion. And rumours of minciag, neisis, tyffish and pethau melys. How many of these are valid moves in Scrabble Yn Gymraeg?

But other than regional stuff, personality is a big one. In any given tongue, everyone tends to have their own personal micro-dialect, as it were. Part of the language learning process is finding it – refining your personality in the NEW (to you) language. Linguists might have a proper term for this. And it includes individual word choices (UPDATE: The word is idiolect.)

I resigned myself to being known of and thought of as a dysgwr (learner). Although at the very beginning I did entertain fancies of privately learning and emerging as a fully formed siaradwr Cymraeg, there’s no way it could happen like that. So I have to blunder about in public parading my peculiar accent, being all wonky, getting words wrong and enduring the laughs. Actually I like the laughs.

This included an interview for the Deffro’r Dinas column in Y Cymro (a newspaper) and a spot on Uned 5 (a TV show) to talk about Sleeveface in my clumsy pidgin Welsh.

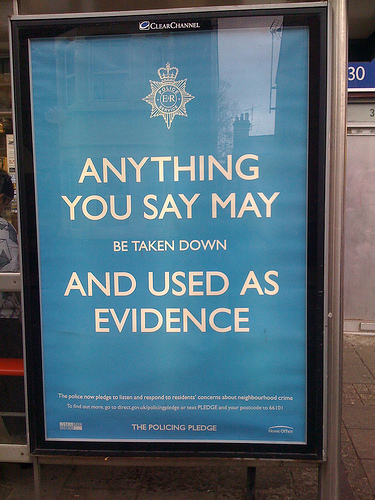

A couple of times I’ve been told I speak like a public warning sign.

Also, drud (expensive) and rhad (cheap) used to get mixed up, as did gwr (husband) and gwraig (wife) – not helped by their proximity in my course notes. If I were the kind of guy that gets embarrassed, this kind of thing would be a problem. Particularly when I casually referred to my female tutor’s child as FY mab (MY son).

But if I was going to be a blundering learner I could at least pick words that sounded ultra-Welsh. So why would I say lico or licio when I could say hoffi (like)? That’s “like” as in “like”, to enjoy or approve – not a kids-overheard-conversing-on-a-bus like… As much as I might amuse myself (and probably myself alone) to pepper my discourse with “fel” or “megis” as I suspect Quentin Tarantino would if he were ever to learn Welsh.

Unlike some, it wasn’t an aversion to loanwords or some romantic notion of “pure Welsh”. That might mean cutting out words like cefndir (background), which smell slightly of English too. (That was just a hunch, but it seems a bit like the thing where “secretary general” smells of Anglo-Norman.) No, I never struggled with these things. Language has always been a mishmash. What are you going to do, cut out the Latin?

Hey! Some words are almost the same all around Europe now. Which is old news. Siocled (chocolate) springs to mind.

It was more about trying to squeeze as much new and exciting Welsh knowledge into a sentence as possible. Thus, warming to my new policy, I dredged up partly forgotten placenames like Trelluest (Grangetown) and Caerliwelydd (Carlisle). And zoomed into saying things like cyfaill (friend) and cyfeillion (friends) instead of ffrind and ffrindiau.

Hey everybody, I’m speaking the Welsh! You can’t get Welshier because I just cut ffrindiau right out of there. Almost literally – thanks to my new found zeal. I eventually chilled out and started using both. I’m told cyfeillion is a bit formal, like the kind of word you’d use in a speech. That’s OK for me. It sits comfortably as I have a personal fondness for the uncommon, the archaic and the perverse. That goes for any language. It’s in my DNA.

When I was chatting at the Eisteddfod I heard someone conjugate lico to make Licwn i (I would like) – albeit not while onstage in the main pavilion. Ergo new outlook. Besides licio is OLD, I heard that they use it in Patagonia, which is a yardstick of OK for these matters. Heh!

One personal trait which runs deeper is that I cannot abide any trace of twee. If there could be a trump card for Carl Morris it would have a rating of 0/10 for tweeness. If the name of the game is twee, then I lose – but I figure I gain so much more. So whoever cooked up popty ping (microwave oven) must feel highly deserving of some kind of award. But not from me. Unless I’m giving an award in recognition of their massive twee face.

In English, I have trouble with “bubble and squeak” for the Bank Holiday Monday breakfast meal. It’s tasty but I cannot allow this ghastly set of sounds to grace my lips. Similarly “I like to cook spag bol in my des res with all mod cons.” is an example of a sentence I would never use. I consider myself a self-respecting human being and only quote it here in mockery of the non-self-respecting.

Obviously it’s not for me to prescribe how anyone else should use language. But neither is it for me to prevent anyone talking like a douchebag.

In among other subjects, I think I’ll MUTATE next time. Ngh!

Mmmmmutations. Don’t hate them. Love them.

Sometimes I feel as if I’m always playing catch-up.

Sometimes I feel as if I’m always playing catch-up.